Five North Star Metrics that drive real subscription growth

The key metrics that lead to sustainable subscription growth.

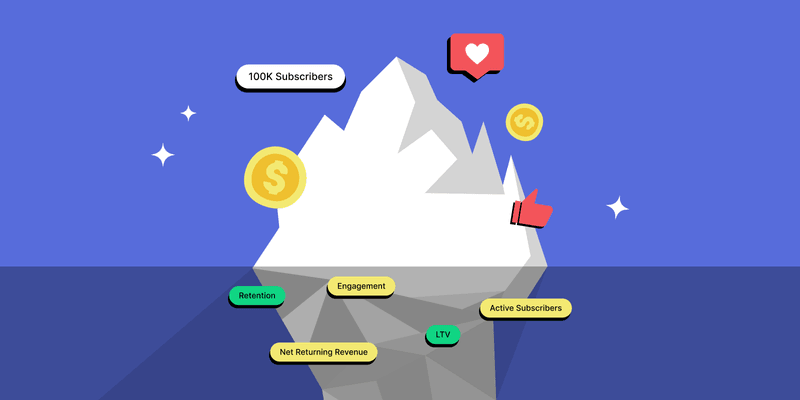

When it comes to determining a North Star Metric (NSM), your most important metric, I’ve been loud about my distaste for the focus on revenue in isolation. It’s not been subtle, but I stand behind it. But there is another metric that is easy to focus on accidentally, and I’ve been guilty of this one as well: your number of subscribers.

Both metrics are risky to focus on, and we will look at why and what metrics are a better NSM for subscription apps. Sadly, there is no one answer, as each metric has its pros and cons. By the end of this article, you’ll know some strong contenders to help you work out the right metric for yourself based on the type of app you are working on and what drives value for customers.

Why focusing on only revenue will hold you back

Companies that get caught up on revenue focus only on what drives value for them and helps them to hit that short-term revenue target. It doesn’t focus on what a good NSM should be, which is a reflection of value for both you and your end customer.

For example, in chasing revenue, you might end up aggressively pushing upsells and ultimately worsening the experience for customers. Or, if you are focusing on monthly revenue, you may rely on discounts to chase that revenue goal.

Focus areas like improving the app for long-term retention get pushed to the background because they take longer to show up in terms of revenue.

It’s not to say revenue doesn’t matter at all. When you choose a metric like this, the end result is naturally revenue, but revenue is not the measure of success. You will still likely look at annual revenue to indicate if you are going in the right direction.

Cedric Yarish is the User Acquisition Lead for Photoroom, a photo and video editing app, and the co-founder of AdManage. He explains it as the following:

“If it’s not going in the right direction, you use it as a blended point of view. Are we making enough money? Are we profitable? It’s more of a sign we have potentially messed up and need to dive deeper. Especially looking at it over time to see how it is varying.”

Should you focus on total subscribers instead?

So we shouldn’t use revenue as our North Star Metric, but what about the number of subscribers? Initially, I leaned towards this metric with the logic that if they weren’t active they would cancel their subscription. However, I’ve seen similar challenges to revenue when using total subscribers as a metric.

Let’s look at a hypothetical example. App A & B charge the exact same amount for their app subscription and are extremely similar in most aspects. However, App A has 40,000 subscribers, while App B has 35,000 subscribers. Which one is better?

Obviously, app A, right? They are bigger, and given their similar pricing model, their revenue is thus likely to be higher.

However, when we then break down the subscribers into three categories:

- Inactive subscribers (have not used the app in the last 30 days)

- Low-engaged subscribers (used it only once or twice in the last 30 days)

- High-engaged subscribers (used it three or more times in the last 30 days)

We see the following:

Well, that changes things! App A actually has a far higher inactive subscriber base, and so while they might be earning more revenue now and appear to be larger, they have a less healthy business. Those inactive subscribers are unlikely to be receiving any value from the app and are likely to churn. This makes it unattractive to communicate with them, as it will negatively impact the overall goal of total subscribers.

Not only that, but those subscribers are unlikely to be referring you to others (assuming you are an app where referral is important and common), meaning your new subscriber growth may also be impacted.

As a result, if we think in terms of Lifetime Value and what the average is per group, the potential value of App A is lower than B.

If we calculate the total LTV per app, it works out as follows:

App A = (22,000 x £40) + (9,000 x £65) + (9000 x £120) = £2,545,000

App B = (10,500 x £40) + (12,000 x £65) + (17000 x £120) = £3,240,000

All in all, growth for App A will be harder, with higher churn, lower engagement, and fewer referrals. Now, this is an oversimplified example, of course, but it just highlights how the wrong metrics can send us in the wrong direction.

So, let’s consider alternative metrics that encourage better behavior. We won’t cover all metrics relevant for apps, but rather dive deeper into potential North Star Metrics. No metric is perfect, and so we will look at the strengths and limitations of each option.

Active Subscribers

You can partly solve this by focusing only on subscribers that you deem active. Let’s go back to App A and B and say that high engaged customers are deemed as active, then their new metrics would be:

While App A is smaller, they do have a bigger pool of potential subscribers to push to active and can focus their efforts on this. They won’t be afraid of communicating with those inactive subscribers as they know that getting more active customers will involve some churning, but that’s okay. They would have churned anyway. They’ll also focus more on understanding and nurturing those active subscribers to keep them happy and onboard. As a result, this metric delivers value for both customers and the company.

We can already see healthier behavior start to emerge from this metric vs total subscribers. It’s an easy-to-understand and user-focused metric. Additionally, the whole company has the potential to impact it, from acquisition to activation to retention and referral. However, it does require one key element: defining what is active.

I worked with a wellness app where we saw the most engaged subscribers were active at least twice in the last 14 days. However, there was another subgroup of subscribers who only used the app once every month or two, but in those moments, it provided so much value that they’d been committed subscribers for years.

It’s part of the balance you need to find. You can’t focus on every form of active subscribers, or you won’t notice people slipping into those lower engagement groups and being at higher risk of churn. Again, look at the Lifetime Value for low-engaged and high-engaged subscribers for App A and B.

So it’s finding a balance where your active subscribers capture your main JTBD that drives the majority of your monetization. That way, you can balance focusing on a big enough group that will drive revenue and value for your company but also not too big that you miss churn risks.

There is another potential disadvantage with this metric: it doesn’t look at revenue in terms of how much those subscribers are spending and what type of subscriptions they have. With the types of subscriptions, the team is likely to focus more on longer-term subscription options, such as driving more annual subscriptions, because it will make hitting active subscriber targets easier.

However, there’s an exception to this. Apps like Duolingo, which offer tiers of spending (Duolingo Super vs Duolingo Max), won’t necessarily be incentivized to push more subscribers to Max (the higher-tiered subscription) if Duolingo Super subscribers are equally active and retain well. For apps like these, focusing on Net Returning Revenue might be better, which we will cover later on.

Core-Usage Metrics

With an engagement-focused metric, you are focusing on actions taken within the app, but you aren’t focused on the number of users using them, instead, the total amount of engagement. There are reports of multiple larger subscription apps using such metrics as their North Star Metric. MemberSpace shares a few examples:

- Spotify – Time spent listening

- Slack – Number of messages sent

- Dropbox – Number of files uploaded

- Zoom – Average weekly hosted meetings

With these metrics, the focus is specifically on how the app provides value and continuously drives value. We saw with the active subscribers metric that subscribers are bucketed into active or not. With the balance of active enough to retain and not active enough, it misses the nuances and the value of driving even more activity. Core usage or engagement metrics solve this issue: more activity = more value delivered. This is accompanied by the assumption that this leads to value for the company in terms of revenue.

Engagement metrics naturally lead to a focus on retention and the most active customers, as they are often the ones that drive engagement. Hanna Greveilus, CPO of Golf Gamebook, a golf scorecard and social app, says they use the following NSM:

“One of the key metrics we use as our north star is the usage of our most appreciated premium feature (HCP rounds); how often premium users engage with our most appreciated premium feature. We focus on this because it directly ties to subscription retention: naturally, the more value users derive from the premium experience, the more likely they are to stick around.”

The reason they chose this is the focus on retention. Hanna used to see a lot of focus on the top of the funnel:

“Over the past decade, I’ve watched subscription companies evolve from an obsession with early conversion metrics—D0, D1, and D7—to a broader focus on long-term success. While those initial conversion rates are still critical, the industry is increasingly prioritizing metrics that paint a more holistic picture of sustainable growth. One metric that’s been gaining serious traction—unsurprisingly, given the shift from ‘growth at all costs’ to today’s profitability-first mindset—is subscription retention. Retention isn’t just about keeping subscribers around; it’s the strongest indicator of whether you’re truly delivering ongoing value.”

These metrics also encourage a focus on acquisition and driving customers to get value out of the product. As much as we want an NSM that focuses on retention, as Hanna says, we need to be conscious of the importance of a metric that captures a focus on acquisition, too:

“Focusing solely on retention can have its downsides—sometimes, you risk neglecting the top of the funnel or over-optimizing for short-term gains. Retention is the glue, but without acquisition, there’s nothing to stick around.”

Core usage metrics help with this. Considering Spotify as another example, their core usage NSM is time spent listening. Everything they do is to help new and existing customers find content that they enjoy. Those new users count as engagements, and as such, they help contribute to that metric. At the same time, to drive retention usage, they push podcasts and audiobooks more these days as these are longer forms of content their subscribers can consume.

There will again be that smaller risk of a reduced focus on new customer acquisition as they won’t be contributing as much to that engagement metric.

However, there can be a disconnect from revenue for subscription apps with a freemium model. It’s great if you have very active free subscribers, but that won’t keep the company afloat. Also, pushing a customer too much to engage can be exhausting. I’ve run away from the Duolingo Owl more than once because of its near-obsessive pushes. Ironically though, it seems Duolingo doesn’t use a core-usage metric, but an active user metric. I guess the owl is just going off the rails, then.

Active Users

If you take an active subscriber goal and combine it with a core usage metric, you basically get an active user goal. This goal includes all engaged users, whether they’ve subscribed or not. MemberSpace reports Duolingo’s metric to be Daily Active Users (ACU) —no wonder the owl is pushy if it needs people to engage every day. Frequency, just like with Active Subscribers, will depend on your app��’s engagement and could also be weekly, monthly, or a completely different time period.

With subscription apps, using active users instead of active subscribers only makes sense if you have a free trial or freemium model. In my opinion, it makes more sense for the second one as there may be users using your product for a longer period of time for free, and keeping them engaged increases the possibility they’ll convert to paid. This is probably why Duolingo uses this metric, as those using it for free on a daily basis are most likely to convert to paid.

There is a secondary benefit of this metric over active subscribers in how it helps with driving referrals. While you can use a referral program for your subscribers, I’ve found that natural word-of-mouth occurs far more frequently with a free version of your app than paid. So, those non-paying users may also support you in acquiring new customers.

While active users, depending on the frequency, reduce the overly pushing customers risk that core usage metrics have (as each user is counted when they engage, not how often), it still has similar risks to usage metrics in that it can be a step away from monetization and the same risk of active subscribers that it buckets all subscribers into one category. This isn’t just about undervaluing very active users but also overvaluing less active users.

Carmen Albisteanu, Senior Growth Analyst at Salt Bank, highlights this issue:

“In our case, our North Star Metric is definitely active customers (as in actually using their bank account, cash in/cash out). From these, we have another segment: customers who haven’t brought any money or done any transaction (no cash in or out) for a specific interval of time. These are still counted as active, but becoming dormant. And we also have those who were never activated (no transaction in our out).

The disadvantage is that, for example, a customer who opened their account, then added some money (became active by doing so), and then moved all their money to a deposit right away and didn’t do any other transaction is considered active, even if he’s only using the account for the interest rate that he’ll get after the deposit maturity date.”

As a result, they are looking to find a better active user metric, ideally a measure of whether they are a person’s primary bank:

“Another thing we measure (but it’s more tricky) is the extent to which customers use us as a primary bank. We work this out through signals such as receiving their paycheck, paying their utility bills, paying their groceries, their subscriptions, etc.”

As Carmen highlighted, this is a tricky one to measure, but the concept is an interesting one. For active subscribers or users, could you capture a metric that highlights you’ve taken up a more permanent or key role in their lives?

Take a fitness app. In the onboarding, you capture how often someone wants to or does the type of workout you offer. In this case, you could define active as relative to what suggests they use you for the majority of their workouts, in that they aren’t using another app or solution for working out. It wouldn’t be easy to figure out, but it would really capture that you are delivering value for that customer and making yourself a core part of their lives. So, I like the fact that Salt Bank tries to look at this and also focuses on optimizing for those types of users.

Now, with all these metrics, we’ve focused heavily on user activity and value to users, but there are two metrics that focus on retention but capture better the financial health of a company. These are Net Returning Revenue and Realized Lifetime Value per Paying Customer.

Net Returning Revenue

Net Returning Revenue (NRR) takes the revenue metric but instead focuses only on existing customers over a certain time period. It looks at how revenue from existing customers is growing over time. The way this is calculated is as follows:

Net Returning Revenue = Total Returning Customer Revenue – (Returns + Discounts + Allowances)

Now, this number can be negative, with the churn of existing customers exceeding the gains in revenue over time and upsells, as Eric Crowley shares in this Sub Club Podcast episode. He also gives an example of how this can be improved over time as a company works on churn and also adds other plans that bring on new customers, as Spotify has done with their family plan.

If we go back to the Duolingo example, using Net Returning Revenue would encourage a focus on Max, especially if Max has lower churn. Not only that, but it would also value all activities to drive more revenue from fewer subscribers than the previous metric would.

It gives a better indication of financial health than active subscribers might and ensures that the focus remains strong on retaining customers vs new customers.

However, a risk is that the lack of focus on customer revenue might discourage a focus on acquisition to drive growth. I’ll be honest with you, though: I’ve rarely met a company that doesn’t focus enough on acquisition. I am [thankfully] yet to find one. I don’t believe there is too much harm in the metric prioritizing retention activities over acquisition activities.

However, it does go a step further away from the value for the customers, with the risk of the situation we saw with Companies A and B being higher. NRR isn’t as focused on what drives value for the end customer. It can also be strangely harder to measure than you expect because revenue occurs at multiple different time points and can also even go down suddenly, such as through refunds.

Additionally, it doesn’t say anything about predicted spend, e.g., you might have customers that spend more in the short term but don’t stick around. This is where the next metric’s strength lies.

Realized Lifetime Value per Paying Customer

Realized Lifetime Value per paying customer, a metric that RevenueCat reports on, can also be a strong guide to:

- Retain customers over time

- Grow their value both in terms of shorter-term revenue (e.g., upsells)

- Focus on the most profitable customers

It’s calculated by looking at the actual revenue (minus refunds) that was generated by a customer cohort, divided by the number of customers in that cohort.

Taking things back to Photoroom, Cedric Yarish explains how the metric plays a role in acquisition decisions:

“The realized LTV per Paying Customer is key as it tells us how much we can pay per customer. We usually also break it down per country because it varies greatly. We combine that with trial conversion rate to determine what we bid on Facebook.”

While Golf Gamebook uses a core-usage metric as their NSM, they also look closely at LTV, especially in relation to acquisition costs. This is how Hanna Grevelius explains it:

“Companies that win in the long run are those that can extend customer lifetime value while keeping acquisition costs in check.”

LTV is a strange one as an NSM, as just focusing on LTV says nothing about your overall growth, but especially in the beginning, it can be a valuable metric in ensuring you strive for profitable acquisition and retention. If you then combine it with the number of users at that LTV, you can get an indicator of how the value of your app for users and your business is growing, as we saw with the earlier calculations, working out the total LTV (also known as the combined LTV).

There are two more challenges with LTV. The first relates to the same one as Net Returning Revenue: spend doesn’t equal value. You could still have inactive customers who have forgotten their subscription or subscribed to an annual subscription without using it.

The second is that with Realized vs Predicted LTV, it’s a lagging indicator. It only accounts for what is realized (as the name suggests), making it harder to measure and see the impact of actions toward improving it, as it may take months or even longer to be confident it has actually improved.

Finding the right metric for you

When choosing a guiding metric, there is no right or wrong answer; it will always depend on your company and what drives a strong focus on longer-term value for your customers while providing value for you. Here is a summary of the metrics we covered and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

| Metric | Definition | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal for |

| Active Subscribers | All subscribers that have met a defined activity level within a specific time period | – Focuses on the most engaged users that drive retention and the highest Lifetime Value – Helps focus on reactivating existing and previous subscribers – Easy to understand for all departments | – Can undervalue certain user groups, e.g., loyal low-engaged subscribers – Doesn’t differentiate in revenue per user or drive focus on additional monetization, e.g., upsells | Apps with clear, recurring usage patterns, not relying on a freemium model |

| Core Usage Metrics | Tracks total engagement with the app’s primary value proposition across all users | – Directly measures and focuses on users getting value from the app – Encourages a focus on both retention and engagement – Easy to understand for all departments | – Disconnected from monetization as it includes free users and doesn’t look at spend per user – Can drive feature burnout- May neglect acquisition efforts and focus on a smaller pool and encouraging their engagement | Apps where the value relates to high activity |

| Active Users | All users (free and paid) that have met a defined activity level within a specific time period | – Drives a focus on building an engaged pool of free users to convert or drive referral – Reduces risk of focusing on over-pushing engagement – Easy to understand for all departments | – Disconnected from monetization as it includes free users and doesn’t look at spend per user – Can undervalue certain user groups, e.g., loyal low-engaged subscribers | Apps with a freemium or trial model where conversion from free to paid is critical but may take longer |

| Net Returning Revenue (NRR) | Revenue from returning customers, factoring in churn, upsells, refunds, and discounts. | – Focuses on the financial health of the company – Focuses on retaining high-value customers and increasing their spend | – Excludes new customers, which may reduce the focus on acquisition – Can be complex to measure (e.g., refunds) – Less focused on the value provided to customers and more focused on monetization | Apps with tiered pricing and/or upsell opportunities |

| (Total) Lifetime Value per Paying Customer | The total revenue customers generate over their entire subscription period, factoring in churn and upgrades | – Focuses on the financial health of the company – Focuses on retaining high-value customers and increasing their spend – Helps in setting profitable CACs | – Difficult to calculate accurately (especially without historical data) – Slow-moving metric, making it harder to see the success or impact of certain actions – Less focused on the value provided to customers and more focused on monetization | Apps with high LTVs and longer retention cycles |

To ensure it gets used on a regular basis, it’s important to consider:

- It’s simple to understand for the whole organization

- Easy to measure on a regular basis

- Will consistently be an important metric not just today but for years to come

- Focus on the full funnel rather than just acquisition

To double-check if a metric will drive the right behavior, I like to ask myself and the team questions like:

- Are everyone’s definition and understanding of the metric the same?

- Are there ways we could achieve this metric and not be successful as a company?

- Could it lead us to focus on the wrong things, e.g., only short-term growth drivers, only on acquisition?

There is no one answer to the perfect NSM, but it’s definitely not revenue and perhaps not the number of subscribers. The examples of the biggest subscription apps highlighted the countless different metrics used as an NSM. However, what they all have in common is that they focus on capturing value for both the customers and the company.

You might also like

- Blog post

Is monetization hurting your app’s user experience?

Don’t trade short-term revenue for long-term trust. How ethical UX can still drive effective monetization.

- Blog post

Meta Ads in 2025: Expert tips from Marcus Burke

Marcus Burke discusses AI, UGC, and the lifespan of ad creatives.

- Blog post

The creative testing system that slashed our CAC (and scaled our spend)

We scaled Meta ad spend by 74.6% and dropped CAC 40%. Here’s how.